Kyla McCallum

Graphic Designer and Illustrator

Student, Master of Library and Information Science

BA in New Media and Digital Design

ky.mccall307@gmail.com

< back

Quick Description

-

The following is an analysis of the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index, or ATU.

-

ATU is a system that classifies folk tales so that folklorists can compare stories across geographic areas.

-

ATU has been criticized for its cultural insensitivity.

The Aarne–Thompson–Uther (or ATU) classification of folk tales began in 1910, when Antti Aarne created the system to organize Scandinavian archival collections (Zipes, 2015). Aarne’s classification was translated and enlarged twice, in 1928 and 1961, by American folklorist Stith Thompson so that scholars could track down variants of the same tale types (Haring, 2006). At the twelfth Congress of the International Society for Folk Narrative Research in 1998, several folklorists gathered to revise the system yet again; Hans-Jörg Uther took the lead, examining and comparing almost 3,500 bibliographic items along with his team of collaborators (Jason, 2006), producing the ATU classification system with the publication of The Types of International Folktales in 2004 (Uther & Folklore Fellows, 2004). There does not appear to be an organization or structure that is continuously responsible for maintaining it, so there are no formal mechanisms for receiving public input.

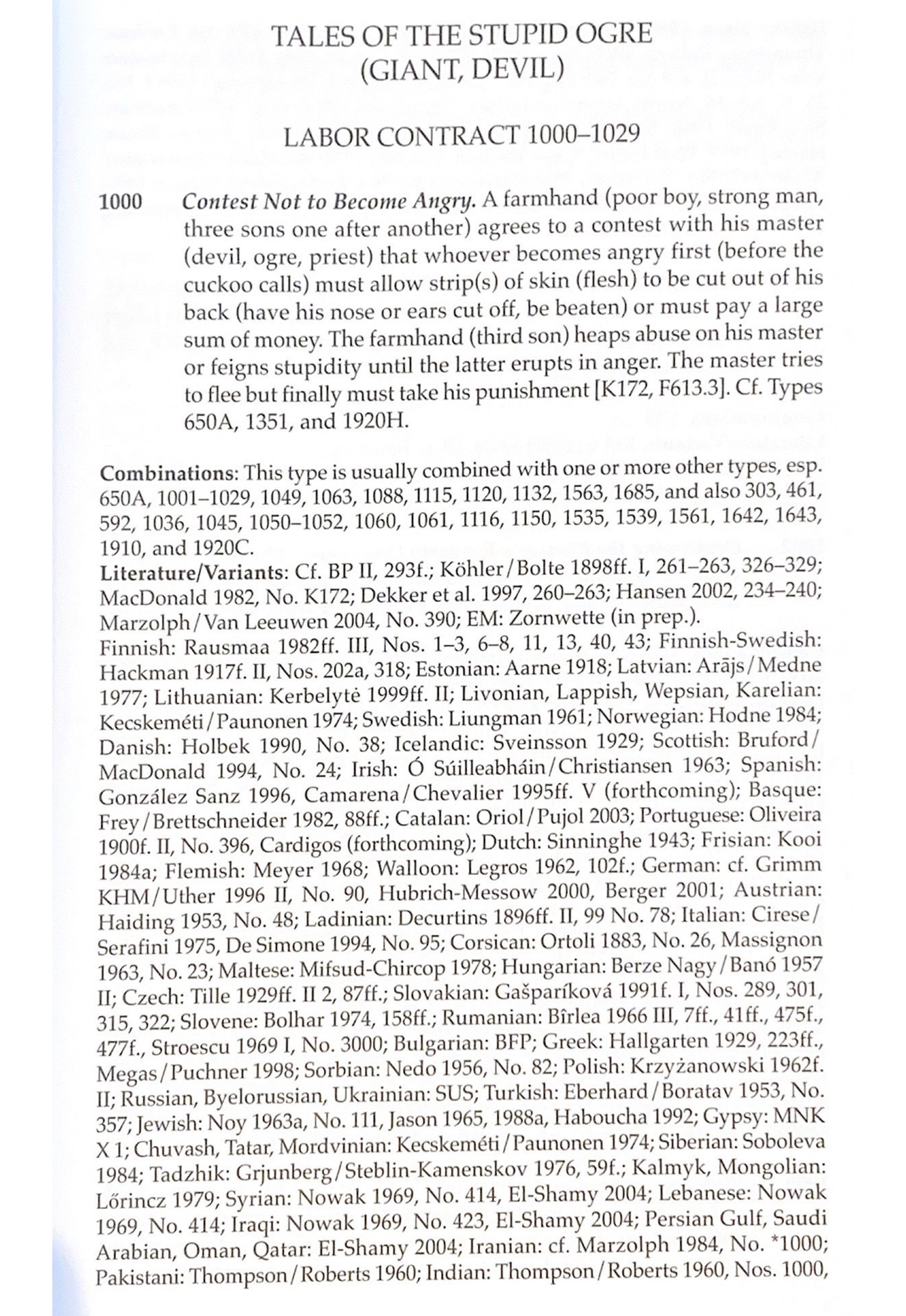

The purpose of ATU is to classify folktales from around the world. Although Aarne started with Scandinavian tales, each successive revision has expanded the geographic scope so that it is no longer limited to the Indo-European world. According to Jeana Jorgensen, a folklorist at UC Berkeley, ATU is best used as a tool for identifying the underlying characteristics of a tale and cross-referencing it to similar tales in different geographic areas (Giaimo, 2017; Crawford, n.d.). Tales are organized by type, then assigned a number and/or letter; Cinderella, for example, is classified under Tales of Magic > Supernatural Helpers with the number 510. The two variants of the Cinderella tale, Persecuted Heroine and Unnatural Love, are further classified as 510A and 510B, respectively (Uther & Folklore Fellows, 2004). In addition to information about a tale type’s principle traits, age, and place of origin, each ATU entry also lists evidence of geographic spread (Haring, 2006). For an example, see figure 1 (Uther & Folklore Fellows, 2004).

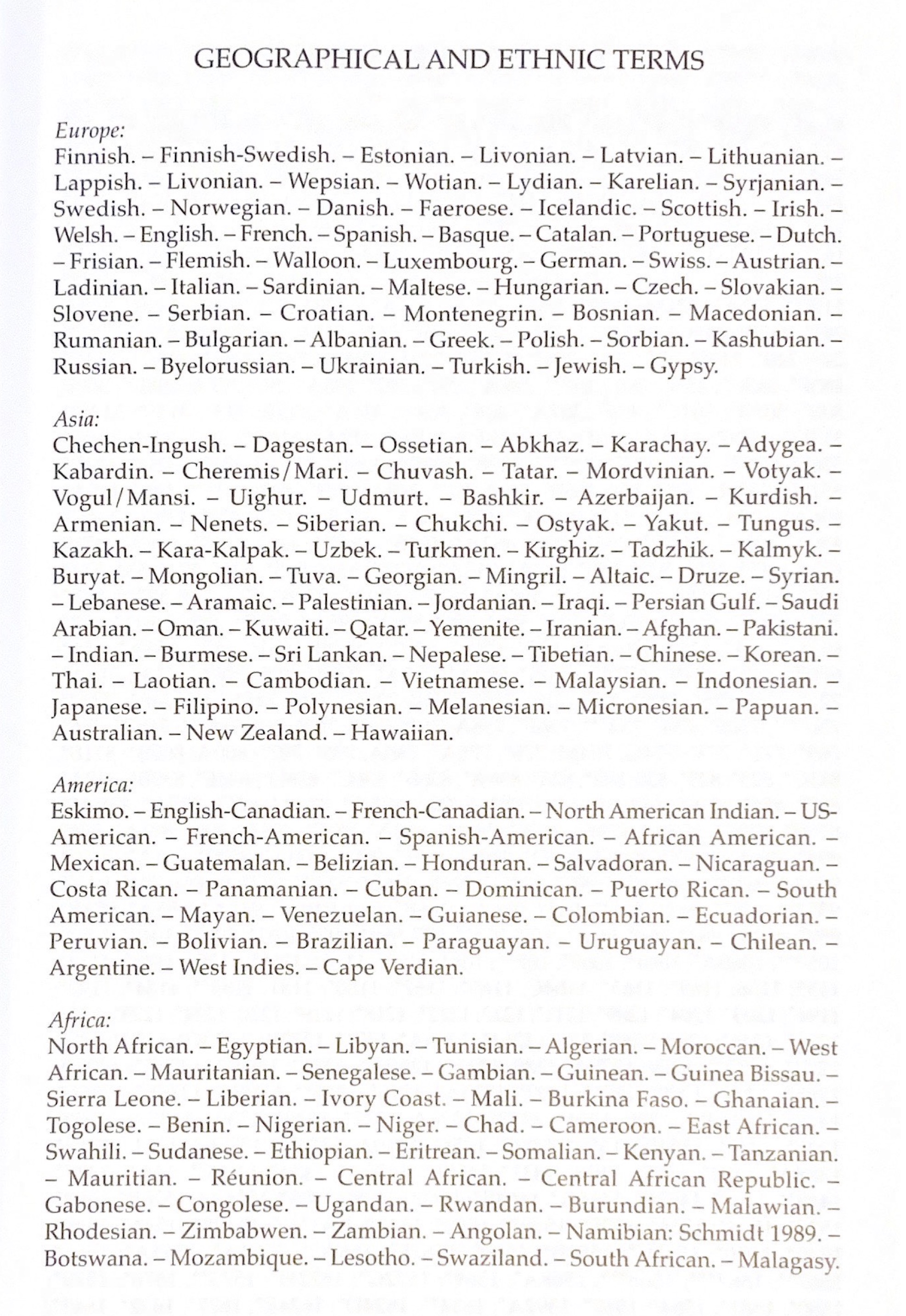

In terms of some obvious issues, a few of the geographic and ethnic terms (see figure 2) are outdated and harmful. This includes Gypsy and Eskimo. Moreover, Aarne originally created the system for Scandinavian tales, which is a potentially limiting structure for tales that originate from other areas. In the introductory chapter of The Types of International Folktales, Uther addresses the insufficient and/or uneven documentation of geographic areas and small ethnic groups (Uther & Folklore Fellows, 2004, p. 7), but Dr. Jorgensen says that ATU is still “not as multicultural as it could be” (Giaimo, 2017). Some critics also acknowledge that the classification of tale types—while aiding in cross-cultural comparison—“promote[s] the universalizing and leveling of texts across cultures,” stripping tales of their contextual complexity (Haase, 2010).

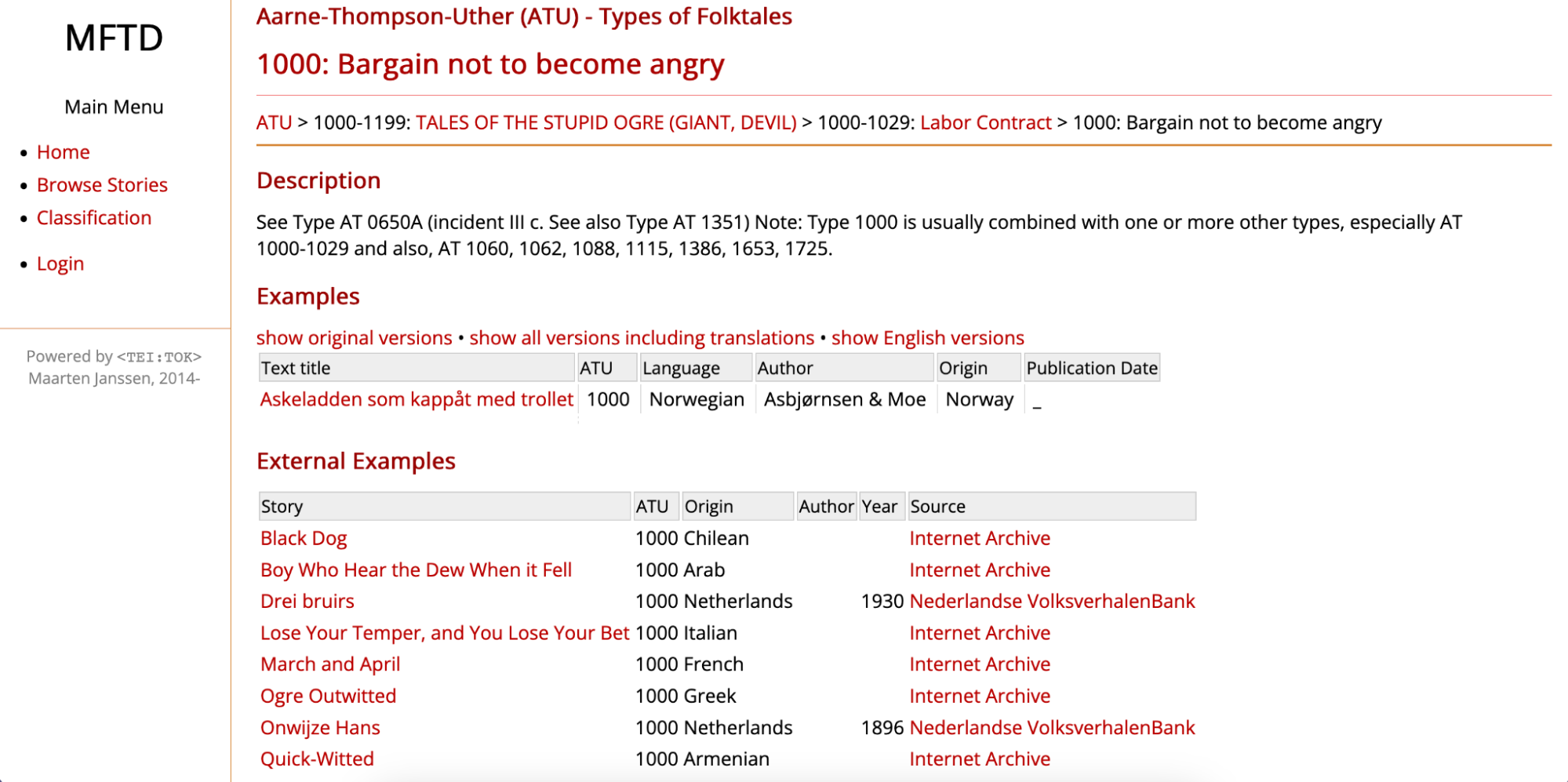

Unfortunately, The Types of International Folktales has not been digitized, although the Multilingual Folk Tale Database (MFTD) contains over 10,000 stories classified according to ATU, with examples and origin listed under tale type to indicate the geographic spread (see figure 3). In comparing figure 1 to figure 3, you can see that significant amounts of information are missing from MFTD, as the purpose is to provide access to tales rather than systematically organize them. Moreover, the MFTD was a community-maintained database up until the site was hacked, so it is not a scholarly source like The Types of International Folktales, although it may be perceived as such.

References

1000: Bargain not to become angry. (n.d.). Multilingual Folk Tale Database. Retrieved October 25, 2023, from http://www.mftd.org/index.php?action=atu&src=atu&id=1000

Crawford, R. (n.d.). Research Guides: Library Research Guide for Folklore and Mythology: Tale-Type and Motif Indices. Retrieved October 22, 2023, from https://guides.library.harvard.edu/folk_and_myth/indices

Giaimo, C. (2017, June 14). The ATU Fable Index: Like the Dewey Decimal System, But With More Ogres. Atlas Obscura. http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/aarne-thompson-uther-tale-type-index-fables-fairy-tales

Haase, D. (2010). Decolonizing Fairy-Tale Studies. Marvels & Tales, 24(1), 17–38.

Haring, L. (2006). The types of international folktales: a classification and bibliography, based on the system of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson (review). Marvels & Tales, 20(1), 103–105. https://doi.org/10.1353/mat.2006.0012

Jason, Heda. (2006). Besprechungen. Fabula, 47(1–2), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1515/FABL.2006.016

Uther, H., & Folklore Fellows. (2004). The types of international folktales: a classification and bibliography, based on the system of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica.

Zipes, J. (2015). Aarne–Thompson index. In The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780199689828.001.0001